What makes a locust kosher? The surprising Torah wisdom behind nature's most misunderstood creatures

Ever wondered why some of your Sephardic friends might casually mention eating locusts while you've never even considered it? Or why the Torah gives us detailed signs for identifying kosher locusts when most of us have never seen one up close?

The laws of kosher locusts reveal something profound about how Torah wisdom works in the real world — and why tradition isn't just about recipes your grandmother passed down.

The four signs that matter

When the Torah discusses kosher locusts, it doesn't leave us guessing. The verse states: "Ach et zeh tochlu m'kol sheretz ha-of, ha-holech al arba... asher lo krayim mi'mal l'reglav, l'nater bahen al ha'aretz." This gives us creatures with both walking legs and jumping legs — but our Sages in the Shulchan Aruch identified four specific signs:

Four walking legs. These are the standard legs used for regular movement, just like any other insect.

Two jumping legs. The powerful hind legs that allow locusts to leap impressive distances — sometimes covering their body length multiple times over.

Wings covering most of the body. Not just tiny wing stubs, but actual wings that provide substantial coverage.

The tradition requirement. Here's where it gets interesting: "U'sh'mo chagav" — it must be called a chagav, a locust, by Jews who have an authentic tradition that this specific species is kosher.

That last sign changes everything. Unlike kosher fish, where fins and scales automatically make it permissible, locusts require something additional — mesorah, tradition.

Why tradition trumps identification

You might think, "If I can identify the four signs, shouldn't that be enough?" But the Torah's approach teaches us something deeper about how knowledge gets transmitted.

Today, only one species carries an authentic tradition: Schistocerca gregaria, known in Hebrew as chagav or arbeh. This is the locust that Yemenite and North African Jews ate for generations — not reluctantly, but as a delicacy. "They ate it like candy," as one expert puts it.

The Yemenite and Moroccan Jews developed sophisticated methods for identification beyond the basic signs. They would flip the locust onto its back and examine the chest plates, which form lines resembling Hebrew letters. Some saw a chet, others a chaf — but these weren't mystical signs. They were practical identification tools passed down through generations of people who knew exactly which species their ancestors consumed.

Meanwhile, Ashkenazi Jews never developed this tradition — not because we had a custom against eating locusts, but because we never encountered them. These creatures thrive in hot, humid climates and simply don't survive in European winters. Our fascinating exploration of kosher locusts shows how geography shaped Jewish food traditions in unexpected ways.

When worlds collide

The modern era created a unique situation. For the first time in Jewish history, Ashkenazi Jews living in Israel encountered Sephardic Jews with authentic locust traditions. This raised a practical question: Can an Ashkenazi Jew learn this tradition and begin eating locusts?

The answer reveals the difference between custom (minhag) and knowledge. Unlike kitniot on Pesach, where Ashkenazi Jews maintain their ancestral custom even when living among Sephardim, locust consumption isn't about competing traditions. It's about identifying the correct species.

An Ashkenazi Jew can absolutely learn the mesorah from someone who possesses it. Once you've received authentic instruction in species identification from a Yemenite or Moroccan Jew with the tradition, you've acquired the knowledge necessary to eat kosher locusts.

This principle extends beyond locusts. Sometimes what we think are religious differences are actually knowledge gaps. The Torah provides frameworks for learning and growing, not just for maintaining static positions.

Racing against time

A few years ago, a locust swarm crossed the Mediterranean from Africa to Cyprus, threatening Israel's agriculture. But this crisis sparked something beautiful — a realization that the last generation with firsthand childhood memories of eating locusts in Yemen and Morocco was aging.

Organizers quickly arranged a conference bringing together elderly Jews from these communities. "I remember eating this when I was a kid," they would say, pointing to specimens. "My grandfather used to eat this one." The gathering united Haredim, Modern Orthodox Jews, rabbis, children, and families — all focused on preserving an authentic piece of Jewish tradition.

This wasn't just about food. It was about recognizing that some knowledge exists only in living memory, and once it's gone, it's irretrievable. The mesorah for kosher locusts could have vanished entirely if not for this conscious effort to document and preserve it.

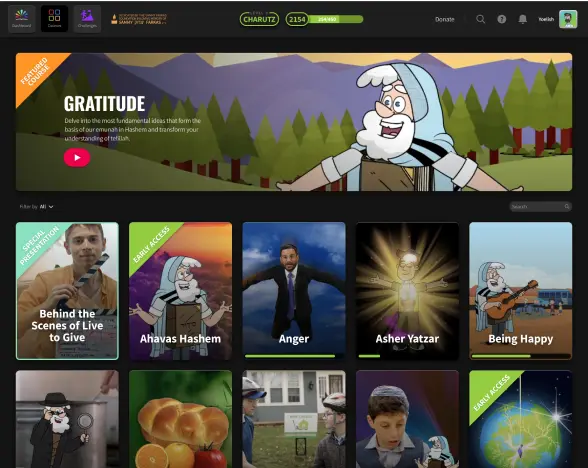

Ready to explore more fascinating corners of Jewish law with your family? Torah Live's collection of engaging videos and interactive challenges makes complex concepts accessible and fun. Sign up free and discover how ancient wisdom comes alive in surprising ways — from locust laws to everyday miracles!