When Your Kid Steals Ice Cream: Teaching Teshuva Through Puppet Wisdom

Your kid eats his brother's snack, looks up with crumb-covered cheeks, and says, "Sorry." You know the look. You also know the apology probably won't last until bedtime. But here's the thing — that moment, messy as it is, holds the seed of one of the most powerful processes in all of Torah: Teshuva.

Why Elul matters for kids too

Rosh Chodesh Elul marks when Moshe went back up Har Sinai after the golden calf. That historical moment set the spiritual tone for every Elul since — these 40 days leading up to Yom Kippur aren't just for adults to feel the weight of the Shofar and Selichos. They're an opportunity to bring our children into the experience rather than having them watch from the sidelines.

The process of Teshuva isn't reserved for adults in Shul on Yom Kippur. Kids can grasp it, and they might grasp it better than we expect — especially when the lesson comes wrapped in humor and a liter of stolen ice cream.

Three steps to real Teshuva

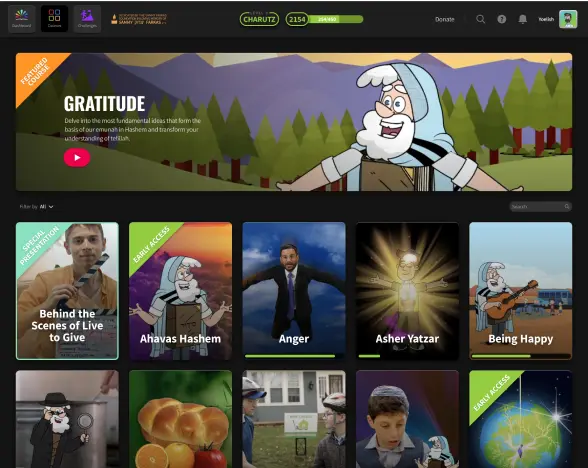

The Shmuppets series uses a puppet character named Gorgle who ate his friend's entire liter of pralines-and-cream ice cream to walk through the three steps of Teshuva in an unforgettable way.

Step one: Recognize what you did wrong. Gorgle admits plainly that he took the ice cream without permission. No excuses, no deflecting, just honest acknowledgment of the aveira.

Step two: Feel genuine remorse. "Oh, do I regret it," Gorgle groans. "On many levels." The tummy ache probably helped drive the point home.

Step three: Commit to not doing it again. And this is where it gets brilliantly real. Gorgle says he can't commit. Why? "There's no more ice cream."

It's funny. Kids will laugh. But it also opens the door to a real conversation: What does it actually mean to commit to change? Is it enough to stop doing something just because the opportunity is gone? Or does true Teshuva require a deeper, internal shift?

These three steps — recognition, regret, and resolution — come straight from the Rambam's Hilchos Teshuva. They're the foundation of the entire Teshuva process. And the Shmuppets make them accessible to even the youngest learners.

Beyond "sorry" — teaching real accountability

Parents hear apologies constantly, but most are just ways kids escape consequences. The real work is showing them that Teshuva is a structured process, not just words. Rabbi Wolbe's approach to character development emphasizes that kids need concrete steps to follow — you can't just tell them to be better. The three Teshuva steps work because they're tangible.

What's powerful is reframing Teshuva entirely. It's not punishment or something scary — it's actually Hashem's gift, a way back that exists specifically because we need it. When kids understand that, especially during Elul, it transforms from something they dread into something they genuinely want to do.

Why humor works

Humor is the vehicle that makes this land. The Shmuppets work because a child watching a puppet confess to stealing ice cream isn't being accused — they're safely observing someone else's process, which lets the lesson sink in without defensiveness. It's the same principle Chazal used with parables, just with felt and googly eyes.

Torah Live's approach works because kids are entertained first and taught second, so they actually ask for more instead of resisting the lesson.

Bringing Teshuva home this Elul

Watch together. Use the Shmuppets video as a conversation starter. Ask your kids what they think about Gorgle's three steps.

Practice with real moments. When conflicts arise, walk through the process together. "What happened? How do you feel about it? What can we do differently next time?"

Create second chances. Make Teshuva tangible with a family "second chance jar" where kids can write down mistakes and commitments to change.

Model it yourself. Share your own Teshuva stories so kids see it's not just for them. Talk about times you made mistakes and how you worked to fix them.

Focus on hope, not fear. Elul should emphasize Hashem's love and forgiveness, not judgment. The second Luchos teach us that failure isn't final — there's always a path back.

The deeper lesson

The genius of using puppets to teach Teshuva isn't just that it's entertaining — it's that it shows kids they already understand the process intuitively. Every time they feel bad about hurting a friend, every time they try to make things right, every time they promise to do better, they're already doing Teshuva.

Our job isn't to teach them something completely foreign. It's to give them the language and structure for what their neshamos already know is right.

This Elul, when your kid inevitably does something wrong and looks up with that familiar expression, remember Gorgle and his ice cream. The tools for real Teshuva are already there. Sometimes we just need a good story — and maybe a few laughs — to help them recognize it.