Yom Kippur: Not What It Seems

Table of Contents

-

Introduction

-

Becoming Angels

-

Why “Baruch Shem” Is Only Loud Once

-

No Shoes, No Ego

-

The Mitzvah To “Not Eat!?”

-

Before Hashem You Shall Be Purified

-

The Happiest “Sad” Day

-

Conclusion: Don’t Miss the Day

Introduction

Yom Kippur. The “Day Of Atonement.” For so many of us, these words feel heavy. Burdensome. And just too “serious.”

But like many things in our amazing religion, Yom Kippur isn’t what it seems.

True, as a people, we receive an amazing level of atonement for our shortcomings on this day. Hashem, in His deep love for us, gives us that amazing gift, and helps us turn around and pursue a more spiritual existence.

But maybe, at our level, a more relatable way to describe it would be – the day that every Jew, without exception, has a chance to pause and take a good look at him/herself.

As we’ll see, Yom Kippur is a day when we actually become something different altogether. We discover a new dimension of ourselves, where we can live at a higher level of existence, something that just wasn’t possible on any other day of the year.

I know, we might not think of it like that. We’re probably used to relating to the day as a solemn day of fasting and confession. But deep down, this day is about returning to who we really are. About remembering that underneath it all, every single Jew is holy and full of amazing potential.

Let’s go!

Becoming Angels

On Yom Kippur, we are told to emulate the angels. It may sound pretty far-fetched. But this idea is actually baked into nearly every custom of this holy day. We’ll see more about some of these points further along in this post, but even just the basics are really shocking:

-

We wear white to display a clear, visual symbol of the angels in Heaven. Now, we don’t really know what angels look like. Not at all. But throughout scripture and rabbinic teachings, angels are described with the color white. Many men wear a white kittle, the long robe usually associated with those leading the prayers. Or by a man about to get married. Or by the person leading the Pesach seder, before he spills grape juice all over it. But this day, it’s for everyone. We’re all at that level. On Yom Kippur, this white robe reminds us of the ability to start anew and achieve the highest level of holiness.

-

We don’t eat or drink – just like the angels, who have no physical needs. We can’t keep it up forever, but for one day, we can do it. We can show ourselves that at our core, this is who we are. Someone once said it perfectly, “we are not physical beings having a spiritual experience. We are spiritual beings having a physical experience.” On this special day, we let our soul take the lead.

-

We don’t wear leather shoes – a luxury symbol and comfort item. Angels don’t need comfort. On the Holiest Day, we step out of our comfort zones and into something higher. At a deeper level, an angel isn’t bound by a “shoe.” That is, an angel can connect directly with the world around, without any intermediary. By living in a pure state, we can also remove the “shoes” we wear, and connect directly to the world around us, without barriers.

-

We say “Baruch Shem” out loud – a line normally whispered after the Shema, out of humility. But on Yom Kippur, we say it aloud, just like the angels who constantly declare Hashem’s glory.

It’s a remarkable transformation. One day a year, we get rid of all this silly “earthly” stuff.

But make no mistake about it – we don’t do this to play a game of dress up. We do it to show that we’ve been playing dress up the whole year, and for one day, we have what it takes to show the world (and ourselves) who we are at the core.

Even with all our mistakes, even with our shortcomings—we are beings of immense holiness, created b’tzelem Elokim (in G-d’s image), with the power to transcend our limits. Yom Kippur reminds us who we were always meant to be.

Why “Baruch Shem” Is Only Loud Once

If we’re like angels on Yom Kippur, and that’s why we say “Baruch Shem Kevod Malchuso L’Olam Va’ed” out loud, you might wonder:

Why do we stop?

Why, during the very first Maariv after the fast—before we’ve even had a sip of water—do we go back to whispering it?

And if we’re supposed to act like angels, what’s going on with the pre-fast meal? We fill ourselves up with kugel and chicken soup and then march into Kol Nidrei with our bellies full, declaring “Baruch Shem” like we’re heavenly beings. Isn't that just a little bit contradictory?

Rav Nota Schiller zt”l, the Rosh Yeshiva of Ohr Somayach, addressed this very question.

His answer: It’s all about where you’re headed.

When we begin Yom Kippur, we’re pointed toward 25 hours of elevation. Our sights are set on becoming more than we are. Even with a full stomach, our mindset is angelic. We’re aiming higher.

But when Yom Kippur ends, even though our fast isn’t technically broken yet, our mindset is already returning to this world. We’re thinking about that first bite of cake, that first cup of cold water. We’re not headed upward anymore—we’re heading back down.

And that, Rav Schiller said, is the real definition of holiness. Not just where you are—but where you’re going. It’s why someone who’s just starting to daven for the first time in years can be on a holier path than someone who has been keeping mitzvos their whole life—but is on autopilot.

Rav Schiller also pointed out the deep significance in how we end the fast—not just how we go through it.

He illustrated this with a story from the world of mountain climbing.

In 1953, Sir Edmund Hillary of New Zealand and Tenzing Norgay, a Sherpa of Nepal, became the first climbers confirmed to reach the summit of Mount Everest. Decades later, the body of British climber George Mallory—who had attempted the climb in 1924—was discovered high on the mountain.

Based on where his body was found, some researchers speculated that Mallory may have reached the summit nearly 30 years before Hillary. But because Mallory never made it back down, we’ll never know for sure.

When Hillary was asked about this possibility, he expressed the idea that ultimately, it doesn't really matter who got to the top first. What matters is that you come back down. The accomplishment lies not just in reaching great heights, but in returning whole.

The message is clear: The true test of growth is not just in moments of inspiration or spiritual elevation, but in how we bring those moments back into everyday life. Not just how we fast—but how we live the day after.

To ascend to the highest levels on Yom Kippur is amazing. But we also have to know how to take the accomplishment and bring it with us into everyday life. We have to eat after the fast but certainly it has to be an entirely different type of eating.

Yom Kippur teaches us to look forward. To step into who we want to be. And to take the first step in that direction with confidence.

No Shoes, No Ego

One of the most curious customs of Yom Kippur is the prohibition against wearing leather shoes.

It’s listed as one of the five inuyim—five forms of abstention we observe on this Holiest Day. But what does footwear have to do with spiritual elevation?

On a practical level, leather was historically a sign of wealth and comfort. Ancient nobles wore leather while the poor went barefoot or wore simpler sandals. By removing our leather shoes, we symbolically strip away pride and luxury—we step into the day with humility.

But there’s something even deeper happening.

In Sefer Shemos (Exodus 3:5), when Moshe Rabbeinu first encounters the burning bush, Hashem tells him, “Shal na’alecha me’al raglecha”—“Remove your shoes from your feet.” Why? Because he was standing on holy ground.

Shoes are what separate us from the earth. They form a barrier between ourselves and our surroundings. When Hashem tells Moshe to remove them, He is saying: This is a place where there can be no barriers. No ego. No pretending.

Yom Kippur is our personal burning bush. A moment of total spiritual presence. We remove the barrier—physical and emotional—between us and the truth. The truth of who we are, what we’ve done, and what we can become.

It’s also the only time in the year when you might see a CEO, a cab driver, and a kollel avreich all wearing the same $5 canvas slippers. On the Day of Atonement, no one stands taller than anyone else. We are all equal before Hashem.

The Mitzvah To “Not Eat?!”

Judaism, for the most part, is a religion that celebrates eating.

Straight up, we like food.

We make blessings before and after food. We sanctify every holiday with a feast. Shabbos is called oneg—delight. And if you ever tried skipping the kiddush cholent, you’d probably be chased down by someone’s bubby (and you’d deserve it, too).

So why, on the Day of Atonement, does Judaism flip the script?

Why is fasting—usually discouraged—suddenly a mitzvah?

The Gemara in Maseches Taanis (11a) says something startling:

"A Torah scholar who fasts is called a sinner.”

Why? Because fasting weakens the body and takes away energy needed for learning Torah, doing mitzvos, or helping others. Generally, Judaism values a healthy, vibrant, active person over someone who’s ascetically depriving themselves.

In fact, the Midrash praises eating on Erev Yom Kippur (the day before the fast) as a mitzvah equal to fasting on the day itself. Preparing to fast is a holy act. We’re not trying to harm our bodies by fasting.

It seems that something else entirely is going on here, as we’ve alluded to already. Generally, fasting is discouraged because it’s harmful to us in some way, whether physically or spiritually. It must be, therefore, that this day – the only Torah-ordained fast day – is somehow beneficial to us.

Yom Kippur is a Shabbos Shabbason (Vayikra 23:32)—a “Sabbath of Sabbaths.” As we’ve already mentioned, it’s the one day a year where the body steps back, and the soul takes over.

We become almost like angels—not by rejecting the physical world, but by remembering that it’s not who we are. There’s no other way to do that other than removing ourselves from this world as much as possible.

Think of it this way: On most days, food is holy because of the brachos we say. On Yom Kippur, fasting is holy because of the presence it creates.

We don’t eat but we are definitely satisfied. We’re “full” of something else. We’re filled with awareness, teshuva, and closeness to Hashem. Our hunger is a tool—not a punishment. It helps us focus on what matters most.

And when the fast ends? Assuming we did it correctly, we should be able to detect the holiness in that first bite of food, and hopefully many other bites after that.

Before Hashem You Shall Be Purified

One of the most powerful verses about Yom Kippur appears in Vayikra, chapter 16:

“Ki ba’yom hazeh yechaper aleichem, l’taher eschem; mikol chatoseichem lifnei Hashem titharu.”

“For on this day, He will atone for you, to purify you; from all your sins, before Hashem you shall be purified.”

Notice what the verse doesn’t say.

It doesn’t say: “If you fast, you’ll be forgiven.”

It doesn’t say: “If you confess enough, or cry enough, or stay in shul the entire day—you’re good.”

It says: On this day, you are purified.

In our world, it might be hard to relate to the idea of “purity.” But clearly, the verse is telling us that something happens to us on this day. The day itself has spiritual power.

Of course, we still have to do our part. The Rambam in Hilchos Teshuva explains that Yom Kippur brings atonement for sins that are “bein adam laMakom—between us and Hashem.” But only if we do teshuva. And for interpersonal sins, there is more to do, as he details there.

But when we do act appropriately, he tells us that the day itself atones for us.

We can think of it like someone enjoying the sunlight. You don’t have to understand it to benefit from its warmth. And perhaps, that’s why even Jews who don’t come to shul all year feel something on Yom Kippur. It’s not just guilt or nostalgia—it’s real kedusha. The gates of Heaven are open. And the day, just by existing, brings us closer to Hashem.

In the Beis HaMikdash, the Kohen Gadol would enter the Kodesh HaKodashim only once a year—on this very day. It wasn’t because he was perfect. It was because Yom Kippur opened a door that didn’t exist the rest of the year.

That door still opens. All we have to do is walk through.

The Happiest “Sad” Day

If someone asked you to describe Yom Kippur in one word, you might say: serious. Or solemn. Or long.

But the Mishnah in Taanis (4:8) says it a little differently:

“There were no days as joyous for the Jewish people as Tu B’Av and Yom Kippur.”

Wait—what?

Yom Kippur… joyous?

It doesn’t exactly look like joy. We’re in shul all day. We’re fasting. There’s a lot of crying. A lot of apologies. No orchestra in sight. No na-nach vans. No awesome chassidish break dancing. Not even that same guitar solo you always hear. Nothing!

So why is it called one of the happiest days in the Jewish calendar?

Because there’s no greater joy than being forgiven. Than being accepted. Than coming home.

On Yom Kippur, Hashem tells us we can come back. We don’t have to keep running away, even with all our wrongdoings. We are encouraged to come as we are, stand before G-d with all our flaws and all our fears and say: “I still want to be close to You.”

And Hashem says: “I still want you.”

That’s simcha. Not the superficial kind. The deep, relieving, soul-level kind. The kind that comes after making things right.

I’m not knocking the na-nach vans and guitar solos, those are still very important. But we’ve got something more joyous happening on Yom Kippur.

And maybe that’s why many shuls sing the final “Lashana Haba’ah B’Yerushalayim” of Ne’ilah with dancing and melody. The gates are closing—but they’re closing with us on the inside.

Maybe that’s why the very next mitzvah after the fast is to start building the sukkah—because we don’t go from Yom Kippur into a spiritual crash. We go from forgiveness into celebration.

The tears of Yom Kippur aren’t tears of fear. They’re tears of release. Of finally letting go of the weight we’ve been carrying all year. Of knowing we are loved, no matter how far we’ve strayed.

Could there be any greater reason to celebrate?

Conclusion: Don’t Miss the Day

Yom Kippur is not just a fast day. It’s not just a marathon of unfamiliar prayers and nice songs.

Yom Kippur is a tremendous gift.

One day each year, the Jewish people are handed something extraordinary: the chance to remember who we really are. The world out there might be turning as usual but our world slows down, and we have a chance to listen to something more important.

The Holiest Day of the year isn’t about distance from G-d—it’s about standing right before Him. “Lifnei Hashem titharu – In front of Hashem, you will be purified.”

Our job is to not let it fly by us. We have to grab on. We can’t miss the chance to pray with honesty. We can’t miss the quiet holiness of white clothes and sock-covered feet. We can’t miss the opportunity to say “Baruch Shem” aloud like the angels.

And we can’t forget that your direction matters more than your location.

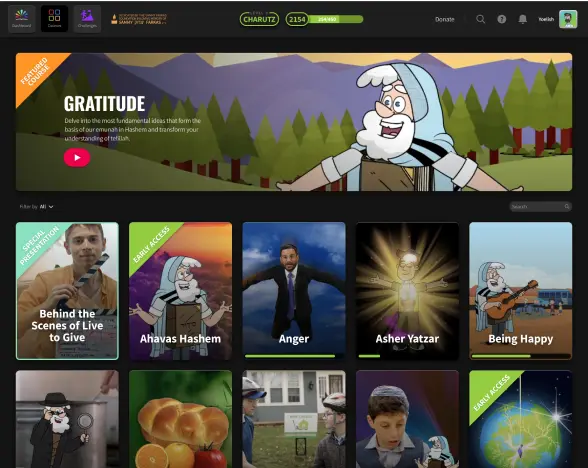

If you haven't yet, check out Torah Live's special Elul series for adults (in partnership with Lachshov) featuring Torah Live's President and the Rosh Yeshiva of Aish HaTorah - Rabbi Yitzchak Berkovits.

May this Yom Kippur—this Day of Atonement, this Jewish Day of Atonement—bring clarity, renewal, and deep inner peace. May we all be sealed in the Book of Life with joy, health, forgiveness, and meaning. G’mar chasimah tovah.