Pesach: A Nation Is Born

Table of Contents

-

Introduction: Living, and Re-Living The Jewish Year

-

The Concept of Freedom in Judaism

-

Slavery in Egypt: More than Physical Bondage

-

Taking Control of Time – “Hachodesh Hazeh Lachem”

-

Chametz vs. Matzah – The Difference of a Moment

-

The Ten Plagues and Moshe’s Gratitude

-

Faith Over Fear: The Ohr HaChaim on Jumping In

-

Pharaoh’s Story: From Wickedness to Teshuvah?

-

Conclusion: Pesach is Just the Beginning

Introduction: Living, and Re-Living The Jewish Year

Pesach, like any story in our holy Torah, isn’t just something that happened once before. The Ramchal (Rabbi Moshe Chaim Luzzatto,Italy/Amsterdam/Israel,1707 - 1746), in his magnum opus “The Way of God (Derech Hashem),” teaches that as we travel through the Jewish year, each calendar date brings with it the same spiritual energy that existed thousands of years ago at that same point in the year.

This means that when each holiday comes, we are reliving the events the holiday represents.

Therefore, when we sit down at the Pesach seder this year, we will not just be commemorating freedom – we will be experiencing it. We will gain a level of freedom, as individuals, and as a nation. We will become less shackled to our own habits, less likely to be reactive, and one step closer to the ultimate redemption of the Jewish people.

Pesach is a blueprint for life. We started out in Egypt as a people loosely held together, without a sense of purpose or clear identity. The experience of the exodus changed everything for us. It was so impactful that we have a mitzvah – a biblical commandment, in effect until today – to teach our children (and ourselves) about all the details of what happened so long ago. This post is a guide for anyone who wants to go deeper into the heart of Pesach. We live in our modern, 21st century world. But if we focus, we’ll travel back in time almost three thousand years. Let’s explore the themes that shape this amazing holiday, and make sure that this year, we walk away from the seder transformed into reframed, refreshed, and re-freed people.

The Concept of Freedom in Judaism

Clearly, a major highlight of Pesach is the story of a nation of slaves being set free. An amazing leader came along – sent by God himself – and miraculously extracted us from under the iron hand of Pharaoh and his minions. The bad guys were destroyed, the good guys left, and everyone lived happily ever after.

But we should wonder – what did that “freedom” look like?

Ask most people what “freedom” means and they’ll probably say “Doing whatever I want.” And that makes sense, right? What could be more free than a person who can just decide to start a business and see it through to the end until he’s got more money than he knows what to do with, ignoring his personal health and relationships along the way...

Most people who would fit the secular idea of a “free man” are actually the opposite. They are enslaved to some sort of urge, craving, or imagined definition of happiness or success. Such a person couldn’t be more enslaved.

Judaism gives us an opposite approach.

Real freedom isn’t about acting without rules. Freedom means the ability to live in a way that is truly connected, and to do what I have to do to gain that connection. It means that there are no forces around me preventing me from pursuing the goals of higher living. It means that the only person I compete with is myself, and I am given the tools and context to win that battle.

We believe in doing what’s right, not what’s easy. Freedom means the ability to pursue that belief.

We are, in fact, still servants. As it says in the Torah, “For the children of Israel are servants to Me… I took them out of the land of Egypt to be servants to Me” (Vayikra 25:55). We serve the Creator of the world, and take advantage of any opportunity to connect to Him. But that type of “servitude” is freedom itself, because via every connection we make to the Almighty, we are building our own future in the world to come.

Taking Control of Time – “Hachodesh Hazeh Lachem”

But let’s step back a little bit before the Jews left Egypt. 15 days to be exact.

On the first day of the month of Nissan, Hashem informed the people of their very first mitzvah.

That’s right, before the light and sound show of Har Sinai, or the spectacle of the splitting of the sea, they were given a very important commandment.

Apparently, it just couldn’t wait. It was that important.

Drum roll please . . . .

“Hachodesh hazeh lachem” — “This month shall be for you the first month of the year.” (Shemos 12:2). Hashem tells Moshe and Aharon to tell the people that from now on, the Jewish year would begin with the month of Nissan.

(I know I know, you assumed that if Rosh Hashana, the Jewish “new year,” which comes out in the month of Tishrei, that would naturally mean that Tishrei is the first month of the year, right? Actually, Tishrei is the seventh month. Yea, it’s weird like that.)

But if we think about it, we’ll see this mitzvah was revolutionary, and represented a massive change for the Jewish people. In fact, this mitzvah is what truly made us a free nation.

When under control of Pharaoh, no one had control of anything in their own life. Egyptian taskmasters dictates when they should work, eat, sleep, work some more. Day wasn’t day, and night wasn’t night. It was all one blur of misery, sparkled with a few glimmering hopes for the future.

With this first mitzvah, Hashem gave us control over time itself. From now on, the Jewish people – as represented by the Jewish religious court and its judges – would declare when each month would start, according to the showing of the new moon. But get this – if we, the Jewish people, wouldn’t declare the new month, it simply wouldn’t happen.

That’s right – our human declaration would somehow influence the positioning of time itself. And Hashem Himself would, as it were, follow suit.

That means that if the Jewish people declared that Nissan had indeed started today, for instance, 15 days from now would be the holiday of Pesach and on that night, the seder would happen, with all associated mitzvos. The Torah’s laws would now cater to our perception of time.

And if on a random Tuesday in the fall, Jewish witnesses declared having seen the new moon of Tishrei, God himself would “change” his plans for the day, and jump into planning every aspect of the new year.

We became in charge of time itself. We gained a certain measure of responsibility and partnership with Hashem.

Now, if that isn’t freedom, I don’t know what is.

Chametz vs. Matzah – The Difference of a Moment

One of the most iconic symbols of Pesach is matzah — the unleavened bread.

Even nowadays, Jews who might otherwise be unaffiliated with classic Judaism, often make an effort to remove chometz from their homes, and eat kosher matzah on the night of the seder.

And even the story behind it is quite well known – the Jews left Egypt in such a rush, their dough didn’t have time to rise, and somehow rose in the sun itself, remaining flat and unleavened.

So, it seems, the only difference between chametz and matzah is time.

And even when we look at the words in Hebrew, the similarity is striking. Matza is spelled “mem - tzadi - heh,” and chametz is spelled “ches - mem - tzadi.”

What’s the difference between a “heh” and a “ches?”

The heh of matzah is open on the middle of one side, while the ches looks almost entirely the same, aside from being closed on that spot.

That little detail becomes everything.

Matzah is flour and water, baked quickly. Chametz is the same, just left to rise. The word “matza” has a little less ink, and “chametz” has a little more.

The line between simplicity and complication is a thin one. Classically, chametz represents ego, puffiness, and comfort. Chametz is what happens when we let things go without intention, and represents that “added-on” part of our personality.

Matza is what happens when we keep things as simple as they can be. It represents faith and humility. It’s connected to the most basic and authentic expression of ourselves.

And in fact, some seforim point that this reality was repeatedly echoed in the bais hamikdash. The Torah forbids adding leavening or honey to any offering (with rare exception). Conversely, there was an obligation to specifically add salt into the mix.

With our earlier explanation in mind, this is easy to understand. Chametz or honey — they’re additives. But salt? Salt brings out what’s already there.

On Pesach, we can connect to a power of simplification. We can remind ourselves that greatness isn’t about becoming someone else — it’s about becoming fully ourselves.

The Ten Plagues and Moshe’s Gratitude

We all know the story: blood, frogs, lice, hail — the Ten Plagues that brought Egypt to its knees.

I’ve even got one of the songs about it in my head right now as I write this. Or is that a frog I hear outside?

Generally speaking, Moshe pulled off each plague with his staff. Don’t try this at home though – it wasn’t any old stick to be sure, and God himself was really rendering the plagues into existence. But for some reason (which we won’t explain today), Moshe had to use his walking stick to give the all-go signal and only then each plague would start.

As the first plague is introduced, we’re told that Aharon strikes the Nile to miraculously turn it into blood.

Yep, Aharon.

Same thing for plague number two, when the river brought forth frogs of various color and sliminess (and croaking frequency).

Yep, Aharon hit the water there also.

And then you know what happened for plague number three, lice? The sand was to be hit – who pulled off that one?

. . . Aharon again. Uh-huh.

If you don’t believe me, check out Exodus 7:19-20, 8:1-2, and 8:12-13. It’s actually all really clear from the verse itself.

This is really important, because when the kids put on a play at the Pesach seder, they better be sure to do this right, otherwise, the play frogs and ketchup colored water won’t miraculously flow into the living room as they should!

Moshe, our great and amazing leader, capable of nearly every super-human feat you can imagine, was told not to be the one to hit the water or sand for these plagues. Why? Because the Nile had saved him as a baby, hiding him in the reeds. And the sand helped him out by hiding the evil Egyptian he had to kill.

Now, if that’s not a lesson in gratitude, I don’t know what is.

Gratitude isn’t about the recipient, really. Don’t get me wrong, it’s nice to be recognized.

But really, the trait of gratitude does more for its owner than for anyone else.

Life isn’t life without a sense of thanking others who’ve helped you.

That’s how we connect to each other. That’s how we keep things in perspective.

And that’s true even to some water and sand. They helped Moshe out – not by doing anything really, other than just being good ole’ sand and water. But Moshe took the opportunity to show his thanks.

If that’s how we treat inanimate things that helped us, how much more so should we recognize the kindness of people. If you’ll look at the person sitting next to you at the seder, I’m willing to bet you can find three reasons to be grateful to them. If you do, tell him or her this idea (you can blame this post for it if you want to).

Faith Over Fear: The Ohr HaChaim on Jumping In

There’s a powerful teaching from the Ohr HaChaim HaKadosh (Rabbi Chaim Ibn Atar, Morocco, 1696 - 1743) about the moment before the sea split.

According to his commentary (Shemot 14:15), it wasn’t so simple to split the sea, even for Moshe. Moshe begins to pray, but Hashem tells him to knock it off: “Why do you cry out to Me? Tell the people to go forward!”

You know, if there’s any Jewish pastime that we use as our go-to method of bringing about salvation, it’s prayer. I can’t think of any other occasion where we learn that Hashem specifically instructed the Jewish people not to pray.

Explains the Ohr HaChaim: In the upper spheres, the Jewish people were on trial. One side of the tribunal argued for the downfall of the Jews. After all, they argued, the Jews had been guilty of idol worship in Egypt just as they Egyptians had. If so, why should they be saved at all, let alone reaching that salvation through the arguably greatest miracle of all time?

Hashem did not argue back, as it were. He left the matter out of His hands, and instead, instructed the Jewish people as to how to circumvent the heavily claim against them. He revealed to them that if they would step into the sea, and show their full trust in God’s salvation, they themselves would bring about the miracle. It wasn’t time to pray – it was time to act.

And so they did. God did not split the sea. The Jewish people did!!!

We can all expect to have some form of struggle in life. Usually, prayer is a good avenue to use (and we should always assume that’s the case). But we should be aware that there are times in life where we have to take action. And if we do, we can be sure to come out on top.

Pharaoh’s Story: From Wickedness to Teshuvah?

A blog about Pesach would be lacking without discussing the villain of the story, Pharaoh. The Egyptian king seems to have been 100% corrupt. He enslaved the Jews. He tortured them. He put them through hardship after hardship. And even when God himself warned him to change his ways, he hardened his heart and ignored ten golden opportunities to move on.

But not every story ends where it starts.

According to Pirkei D’Rabbi Eliezer (Chapter 43), Pharaoh didn’t drown at the sea. He survived, made his way to Nineveh, and eventually became the king. Yes — that Nineveh, the one that later does teshuvah in the days of Yonah.

The above-mentioned source uses Pharaoh as the ultimate display of the power of repentance. If someone as cruel as Pharaoh has the capacity for change, what does that mean for the rest of us? We can’t give up on anyone – Not our friends. Not our kids. Not even ourselves.

But it goes one step further.

Some sources give more detail about the process of Pharoah’s survival. Hashem created a special pocket of air under the sea where he kept Pharoah captive for a full fifty days, giving them the ability to think over some things. He realized – in the deepest way – everything he had done wrong. And he also concluded that there must be a way to do better.

When we think about it, that means that this was the final miracle of the Pesach story. Hashem himself displayed the greatest miracle of all — not the splitting of the sea, but this story of repentance. When Hashem wants someone to repent, he will perform a private miracle to make it happen.

What could be a free-er, happier ending than that?

Conclusion: Pesach is Just the Beginning

Pesach is the story of our birth as a people. Any birth is preceded by an amount of pain. A woman screaming in labor is truly a sign of something amazing about to happen.

It takes effort to break free from the mental and spiritual slavery that holds us back, each one of us at our own level.

It takes patience and persistence to manage our time, to humble ourselves, and to show the proper gratitude.

It takes courage to jump into the sea and believe in our own ability of chance, and never let anything hold us back.

But if we do our part, then we can trust in the words of the Haggadah, that Hashem will help us succeed, “not through an agent, not through an angel, but through His own Honor, directly.”

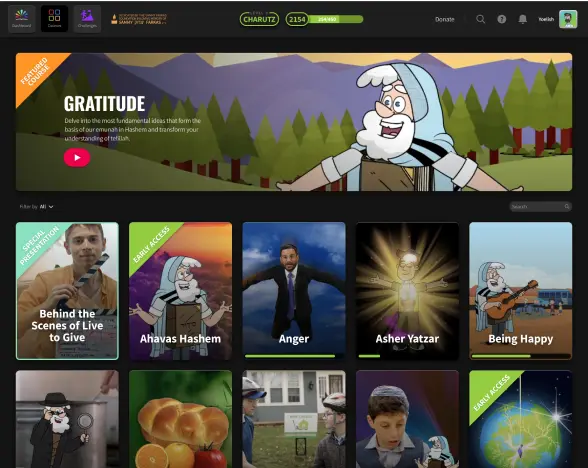

Don't forget to check out Torah Live's courses on Pesach and Hilchos Yom Tov to make sure you're totally prepared for the chag!

As we prepare for Pesach, may these lessons not just stay on the Seder table, but enter our lives. Because the timeless Passover story isn’t a one-time thing – it’s a living guide to how to become truly free in a world of slavery.

Chag kasher v’sameach!